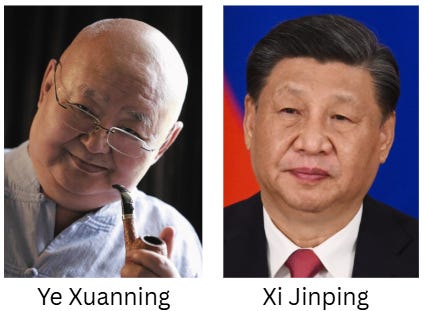

One of the most compelling and underexplored theories about the rise and rule of Xi Jinping, developed exclusively by WideFountain after eight years of intensive research, is that Xi may not have been the true architect of his own ascent or of the signature initiatives that marked his early rule. Instead, the mastermind behind it all may have been Ye Xuanning: the enigmatic intelligence czar, princeling patriarch, and head of the Ye-Xi Clique, a covert network of political warfare specialists embedded within China’s military, intelligence, and party apparatus.

According to this theory, Xi Jinping’s rapid consolidation of power and bold global initiatives between 2012 and 2016 were less a reflection of his personal strength than of Ye Xuanning’s strategic guidance and behind-the-scenes enforcement. And when Ye died in mid-2016, the theory goes, Xi's effectiveness and ambition sharply declined, revealing a leader who without his political benefactor has been unable to chart a clear path forward, either domestically or internationally.

A Theory Rooted in Political Warfare

Ye Xuanning, son of Marshal Ye Jianying and one of the most powerful intelligence operatives in modern Chinese history, was known for his mastery of “unrestricted warfare” a strategy that combines espionage, financial manipulation, propaganda, and organized crime to achieve political objectives.

While many observers saw Xi Jinping’s elevation to General Secretary in 2012 as the result of consensus politics, this theory posits something more calculated: that Ye Xuanning orchestrated targeted investigations and character assassinations against Xi's primary rivals, especially Bo Xilai, Chen Liangyu, and Ling Jihua, (see WideFountain post Ye-Xi Clique, Moving Mountains to Put Xi in Power) effectively clearing a path for Xi to emerge as the compromise candidate, who then became the undisputed leader.

Ye’s position at the nexus of the Central Military Commission, the United Front Work Department, and Chinese military intelligence gave him the reach to make and break careers. As head of the PLA’s General Political Department (GPD), he had the institutional authority to cross ministerial boundaries, interrogate senior secretaries, and access classified information from virtually any corner of the state. This allowed him to gather kompromat, deploy loyal cadres, and neutralize opposition with ease. More importantly, Ye’s deep connections to commercial empires and illicit financial networks gave him the means to fund covert initiatives far beyond the formal state budget.

The Xi Agenda: Engineered by Ye?

From 2012 to 2016, Xi Jinping appeared unstoppable. In quick succession, he:

Launched a high-profile anti-corruption campaign that removed hundreds of senior officials.

Initiated aggressive island-building in the South China Sea, followed by rapid militarization.

Rolled out the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) a trillion-dollar strategy to project Chinese influence through infrastructure and debt diplomacy.

Reformed the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) and took personal control of multiple command centers.

Consolidated power across the Party, state, and military in a way not seen since Mao.

But each of these moves bears the fingerprints of Ye Xuanning’s worldview, especially the emphasis on covert power, preemptive purges, and geopolitical maneuvering through financial entanglement.

Many early BRI projects were driven by opaque, often corrupt funding pipelines, routed through state-owned enterprises with links to Ye-aligned actors like CEFC China Energy and entities associated with Lai Changxing and Ng Lap Seng. The South China Sea campaign was conducted with military secrecy and “plausible deniability”—hallmarks of Ye’s strategic doctrine.

Meanwhile, the anti-corruption campaign, while celebrated in Chinese media, operated with the precision of an internal purge, disproportionately targeting figures linked to rival factions like the Youth League or the Jiang Zemin network.

The Turning Point: Ye’s Death in 2016

Ye Xuanning died in July 2016. And from that point forward, Xi Jinping’s political clarity and strategic momentum appear to dissipate.

In the second half of 2016 and into 2017, Xi’s administration grew more reactive, defensive, and internally focused. Major geopolitical moves slowed. The BRI became plagued by debt defaults, bad publicity, and resistance. Domestically, Xi pushed through a removal of term limits in 2018, but the move drew rare backlash and fear, not awe.

The “Wolf Warrior” diplomacy that emerged around 2019, belligerent, undisciplined, and ineffective, seemed to mark a shift from Ye’s stealthy realism to something closer to nationalist bluster. Without Ye’s stabilizing force, Xi’s inner circle appeared increasingly filled with loyalists but devoid of innovative thinkers or disciplined strategists.

China’s international image deteriorated further during the COVID-19 pandemic, and by the early 2020s, Xi's regime had become increasingly isolated and reactive. Ambitious economic reforms gave way to ideological purges and erratic crackdowns—from tech giants to real estate. Once bold on the global stage, Xi began to avoid foreign summits and retreated into a narrative of inward “struggle” and security paranoia.

Conclusion: Xi Without Ye

This theory does not assert that Xi Jinping was merely a puppet, but rather that his most consequential actions were enabled, and perhaps even architected, by Ye Xuanning, the last great fixer of the revolutionary generation. With Ye’s passing, Xi lost not only a protector and strategist, but the very infrastructure of influence and power projection that had carried him forward.

What has followed is a period marked by stagnation, fear, and acute miscalculation where ambition has been supplanted by repression, and vision by suspicion. In the absence of Ye, elite CCP politics have been dominated by an eerie series of disappearances and suspected murders: the sudden fall, and likely politically motivated detention, of Foreign Minister Qin Gang; the shadowy death of Li Keqiang under mysterious circumstances. These incidents suggest a leadership structure so attenuated it has resorted to violence and secrecy, rather than coherent strategy.

In the years since Ye’s death, Xi has failed to produce a successor, articulate a new national strategy, or establish a lasting global legacy. If this theory holds, his tenure may one day be remembered not for what he built, but for what was only sustained by a now-vanished political machine.

Fascinating. Thanks for all the research. It explains a lot especially what’s been going on here in Canada …

Thank you Ben David for restacking and your referrals!