To understand Xi Jinping’s authoritarian turn, one must look beyond ideology and ambition and consider the unresolved traumas of his youth. Xi grew up during the Cultural Revolution, a period of violent chaos unleashed by Mao Zedong. As a teenager, he witnessed the public humiliation and purge of his father, Xi Zhongxun, once a senior Party leader. Xi himself was denounced, sent to the countryside for “re-education,” and reportedly rejected by the very revolutionary fervor he was told to embrace. These early experiences of betrayal, shame, and powerlessness appear to have hardened into a lifelong obsession with loyalty, control, and ideological purity. Historian Ian Kershaw, in his biography of Hitler, noted that “Personal traumas, especially those rooted in youth, can be transformed, if not addressed, into tyrannical behavior when a man gains absolute power and confuses personal destiny with national fate.” Xi’s China bears the marks of such a transformation: a crackdown on media and intellectual life, a weaponized anti-corruption campaign that purges enemies while protecting allies, and a return to Mao-era tactics that regulate not just behavior but thought. Far from merely replicating Mao’s methods, Xi seems driven by a need to rewrite the humiliations of his past into a triumph of absolute control. His rule may not be solely a political project. It may also be a personal reckoning, imposed on the lives and futures of roughly a billion people.

Media Crack Down

In the early days of his leadership, Xi Jinping moved swiftly to bring China’s media under tighter Party control. In late 2012 and early 2013, shortly after assuming the role of General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party, Xi visited the headquarters of People’s Daily, Xinhua News Agency, and China Central Television (CCTV). These highly publicized visits culminated in a clear and chilling directive: “The media run by the Party must bear the Party’s surname” (党媒姓党), meaning all media must serve the interests of the CCP above all else.

This demand marked a decisive break from even the limited editorial experimentation of the Hu Jintao era. Prominent journalists who had operated with a degree of independence were swiftly targeted. One example is Rui Chenggang, a charismatic CCTV anchor with international ties, who was detained in 2014 and vanished from public life under corruption allegations widely believed to be politically motivated. Another is Qian Gang, a former People’s Daily editor and media scholar, who was effectively silenced for advocating press professionalism and eventually forced out of the public sphere.

Xi’s crackdown crushed remaining hopes for media reform and had a chilling effect across Chinese society. Investigative journalism withered. Online discourse narrowed. Critical voices were replaced by uniform propaganda. In redefining the media as a tool of state power, Xi Jinping not only cemented his control but also undermined public trust, transparency, and the capacity for self-correction within the Chinese system.

“Turn over your assets”

When Xi Jinping assumed leadership of the Chinese Communist Party in late 2012, he launched a sweeping anti-corruption campaign that targeted thousands of officials, from minor bureaucrats to top Party elites. While the campaign was widely seen as necessary, addressing endemic graft that had eroded public trust, it also functioned as a powerful political purge. Xi used corruption charges selectively to eliminate rivals and consolidate power, cloaking authoritarian ambition in the language of moral rectitude.

According to Desmond Shum, author of Red Roulette, Xi demanded that Party elites surrender their personal wealth to the CCP in the early phase of the campaign (2013–2014). The message was blunt: hand over your assets, or face investigation. This marked a shift in loyalty standards, from mere ideological conformity to financial obedience. Those who complied were spared; those who resisted risked disgrace or imprisonment.

Yet the campaign’s hypocrisy is glaring. Xi himself is closely tied to the Ye-Xi Clique, a powerful network of red princelings. Evidence suggests that members of this faction profited heavily from oil smuggling operations during the 1999–2009 period, after smuggling kingpin Lai Changxing fled to Canada. Rather than being investigated, Xi rose steadily through the ranks, suggesting his faction not only avoided scrutiny, but may have benefited from the very corruption others were punished for.

Experts also suspect that Xi traded leniency for loyalty from many corrupt officials. Rather than being eradicated, much of the seized or "redirected" wealth, potentially from the 1.5 million officials investigated, was funneled into geopolitical priorities. These include Belt and Road projects, gray-zone influence campaigns, and money-laundering schemes in and around the first and second island chains. In this view, Xi’s anti-corruption drive did not dismantle corruption, it nationalized it, turning illicit wealth into a covert war chest for China’s global ambitions.

Document No. 9

In the wake of his rise to power in late 2012, Xi Jinping launched a sweeping ideological campaign to root out what he called the corrosive influence of “Western values” in Chinese society. By 2013, the Party had issued Document No. 9, a secret directive warning against seven dangerous topics: constitutional democracy, universal values, civil society, media freedom, historical nihilism (i.e. criticizing the CCP), neoliberal economics, and judicial independence. Universities and media outlets were ordered to avoid these themes entirely. What followed was an aggressive campaign of intellectual repression, one that extinguished the cautious liberalism that had taken root in elite institutions during the Hu-Wen era.

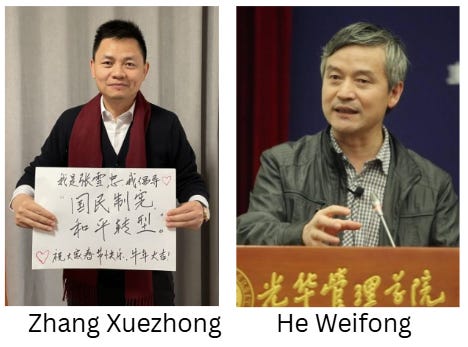

Professors found themselves under surveillance, and students were encouraged to report instructors who broached sensitive topics. Zhang Xuezhong, a constitutional law professor in Shanghai, was among the few who refused to stay silent. He publicly criticized the ban and continued to advocate for constitutionalism, until he was dismissed from his university post in 2013 and later detained in 2020. Others, like legal scholar He Weifang of Peking University, were gradually pushed to the margins of academic life, their writings restricted, and their voices silenced.

The effect on Chinese society was immediate and chilling. Academic freedom shrank. University discussion became mechanical and risk-averse. A generation of students learned that inquiry into justice, rights, or democracy could lead to real consequences. What Xi framed as ideological purification was, in practice, the systematic demolition of China’s fragile space for critical thought, a purge not of enemies, but of ideas.

Xi’s Disappearing Acts

From the earliest years of his rule, Xi Jinping demonstrated a ruthless preference for making perceived disobedience disappear, literally. A chilling pattern emerged: individuals who challenged his authority, embarrassed him, or failed to show unwavering loyalty were not merely sidelined, but often detained in secret, subjected to psychological and physical pressure, and returned to public life only after recanting, or not at all.

Victims ranged widely. Jack Ma, once China’s richest man, vanished from public view for months in 2020 after criticizing financial regulators; he reappeared subdued and stripped of influence. Whitney Duan, the wife of Red Roulette author Desmond Shum, was taken in 2017 and held without charge for years; her sudden phone call in 2021, urging Shum not to speak out, bore the unmistakable tone of coercion. In Hong Kong, publishers connected to tabloid reports about Xi’s alleged mistress, such as Mighty Current’s Gui Minhai, were abducted and reportedly tortured into televised confessions. Even pop stars and tennis players like Hu Na, who defected in the 1980s and was later scrubbed from Chinese history, faced retroactive erasure or intimidation.

Accounts from within China’s “residential surveillance in a designated location” (RSDL) system describe prolonged isolation, sleep deprivation, threats to family, and interrogations designed to break the will. These are not the methods of a confident statesman, they are the tools of a paranoid autocrat.

Xi’s use of forced disappearances and psychological torture suggests a leadership style rooted not in strength, but in deep insecurity and obsession with control. A leader who silences critics through invisible chains reveals more about his own fears than about the threat his targets pose. It is not just repression, it is governance by fear, disguised as stability.

As China is seeking to put an end to Xi’s rule, the next article here will cover Xi’s antipathy for the US.